Thomas Lyons ’21 shares his first impressions of Croatia.

12 am-4 am is a time reserved for the adventurous. Ultramarathon runners attempting to escape the heat of the day’s sun, farmers up with the rooster, long distance truckers searching for exit signs, Deerfield students pulling late night study sessions. Gazing into those early summer morning sunrises are sacred; they connect the few that are awake. Today, (or yesterday? two days ago? I’m not sure, jet lag is throwing us all for a loop) the members of our trip got to witness the birth of a new summer day. Slightly past 11 pm, (Eastern Coast Time) through a smudged airplane window, we watched as the sun rose. How many sunrises had Bosnian refugees or UN officials seen rise over the broken streets of Bosnia, Serbia or Croatia? How many are left to tell those stories? Today, the sun rises over nations separated by both political borders and history; in the 1990’s, the sun rose over a recently broken Yugoslavia and the rays illuminated Serbia’s violent attempts to create the Greater Serbia. During this trip, we will have the opportunity to not only trace the course of the conflicts, talk with survivors and historians, but see how these conflicts affect current relations throughout the Balkans and what the 90’s Yugoslavian wars reveal about the dangers of nationalism today.

Once off the plane and in Zagreb, Croatia, we stopped at Karijola (a pizza restaurant) for lunch. Once pizza had been served and calories proved a temporary antidote to jet lag, we began regaling each other with stories from our middle school days. One story struck me as particularly relevant to our trip. A friend told us that in her New York middle school, a student brought in a kitchen knife and was cutting the zippers of peer’s bags. Though slightly disturbing, the story was a comical one and ended in a student alerting the teacher about the incident, the adult negated the problem and the story ended. However, what if there is no teacher to tell?When your neighbors do more than just cut the zippers off your back packs, when they kill your children and rape your partners, when they send you to concentration camps and leave you in mass graves, what happens when the teachers are looking the other way?

In Love Thy Neighbor by Peter Maass, George Keeney, the state department representative for Bosnia recalled, “My job was to make it appear as though the US was active and concerned about the situation and, at the same time, give no one the impression that the US was actually going to do something significant about it”. Keeney later resigned from his diplomatic position out of principal. Maass writes, “As evidence of widespread torture and murder cascaded into his (Keeney’s) lap in the following weeks, the State Department refused to say “genocide” was occurring. Why the strange reluctance? An acknowledgement would have lain the groundwork for requiring the government to take action in line with its legal obligations under the 1949 UN Convention on the Pre-Obligations and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.” US officials, unwilling to risk the lives of American boys, consciously attempted to uphold a blissful ignorance of the full brutality of the wars. When Bosnians requested arms and foreign intervention (some even asked American fighter pilots to bomb their cities so they could finally be at peace), the US’s neutrality effectively empowered the perpetrators.

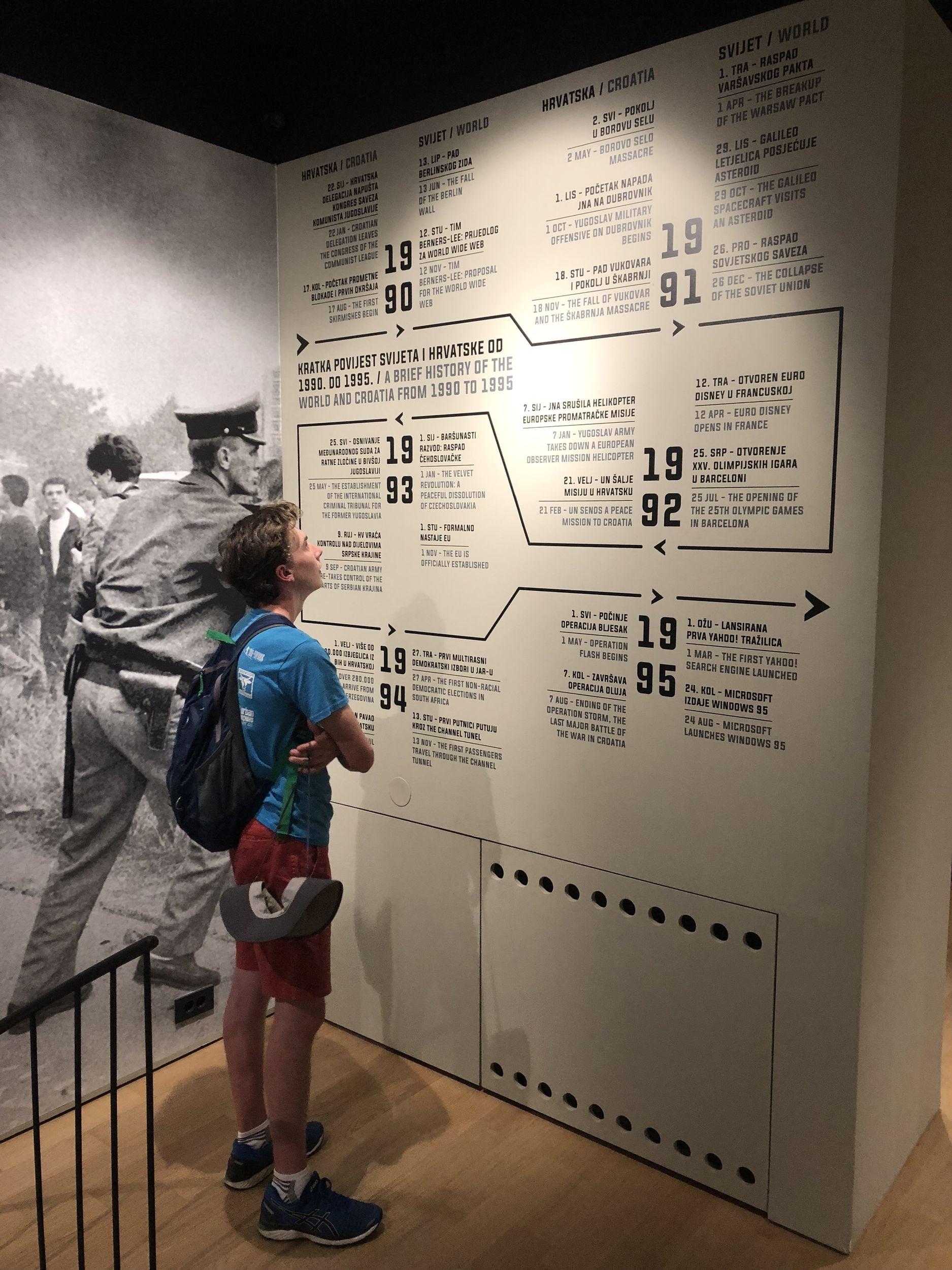

Exploring the complexities of the wars, we arrived in a bunker turned museum exhibit where Luka, a local tour guide and son of a Croatian soldier, shared with us a documentary of the Yugoslav fighting. Ideology and narrative fueled the Yugoslav wars just as much as guns and men. Articulated in the documentary, the power of the battle of perspective became clear when Serbian and Bosnian newscasters giving different reports, sentence for sentence repeated the other’s statements, switching only the country’s names. For example, the Serbian reporter might say “photographs show no evidence that Serbian military committed attacks against civilians” and the Croatian reporter would say “photographs show no evidence that Croatian military committed attacks against civilians”. Though similar, stories and propaganda served as a potent method of inspiration and indoctrination for both sides.

Given time to explore the city, I found myself at what I can best describe in English as a fresh juice/balls of fried dough food stand (my Serbo-Croatian is limited to “hello” and “thank you” at the moment), a strangely enthusiastic man in his late 20’s greeted us (enthusiastic, we learned, because we were his first customers of the day…it was 4:30 pm). We asked him if he knew anyone who fought in the wars. “Practically everyone who’s now over 40” he replied. It is hard to imagine a city where every member of a generation fought. But Zagreb doesn’t have the feel of a war-torn community. Beyoncé songs and Nike ads fill the city streets of Zagreb, and, though more graffiti filled and grittier than the alleys of smaller US cities, one could easily confuse the two upon first glance.

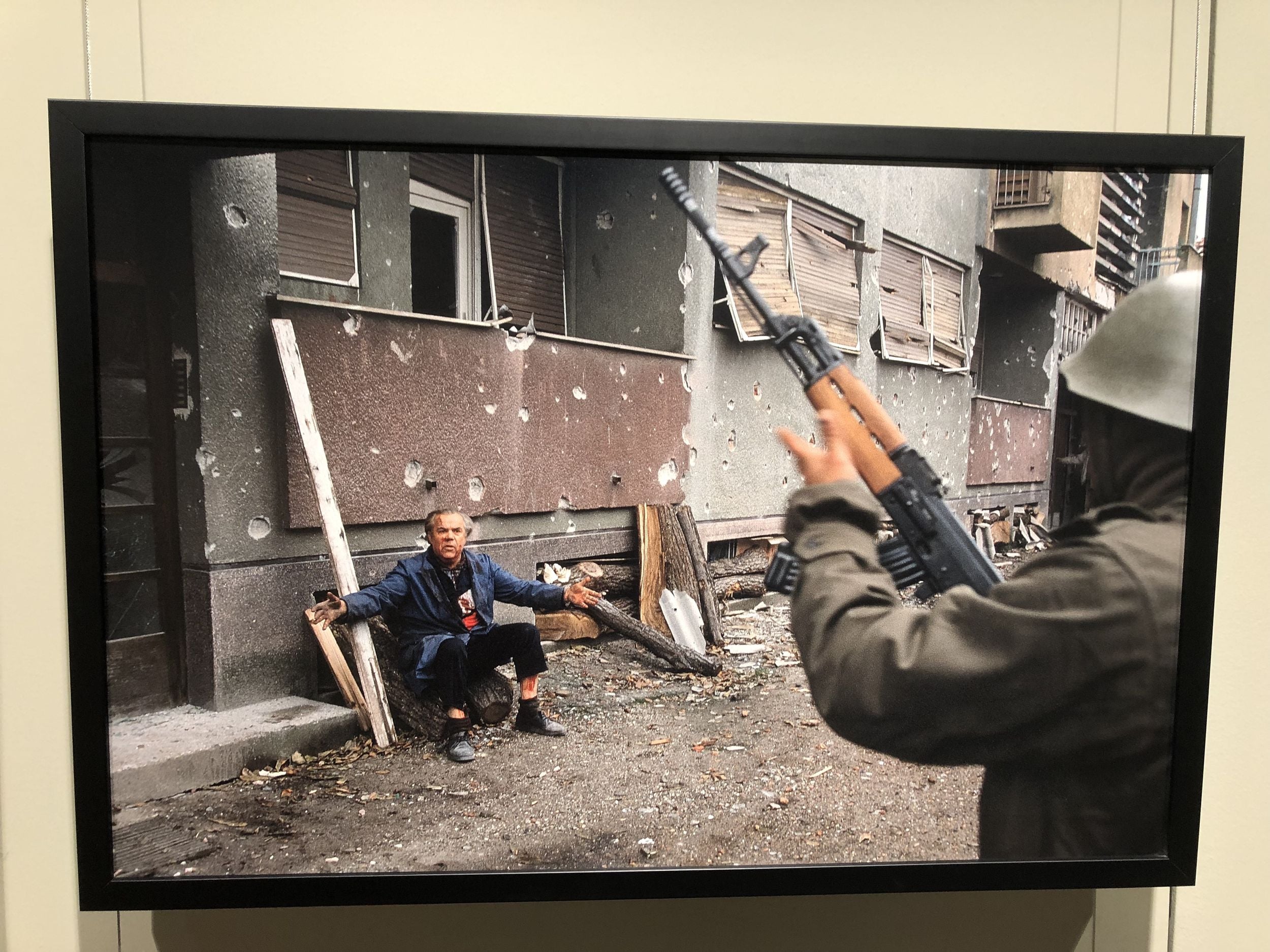

However, even in the developed Balkan’s countries, over 20 years after the wars, tensions between Serbia and Croatia remain high. Mak, our local tour guide, warned Deerfield students who bought Croatian soccer jerseys not to wear the shirts during the portion of our trip in Serbia. Even just a part of the flag on a jersey is enough to bring back strong emotions about national identity, ethnic cleansing and conflict. But the stray heated encounter with a passionate veteran or nationalist is rare; the majority of the public memory that lives in Zagreb resides in museums. In fact, the city has the most museums per square meter in the world. In the museum of war photography, we saw the conflict and suffering through the eyes of photographers on the ground. In Vukovar 18 taken by Charles Morrison, an Elderly Croatian civilian is bloody and wounded after being forced out of his basement by a hand grenade. He sits on a stump outside his house among the rubble, arms outstretched, frail and pleading, begging for his life in front of a Serbian soldier with a gun. The rubble is what remains of his house, but it is also symbolic of the country. How did the Balkans arrive in this situation? How did neighbor turn murderer? How do good, ordinary people commit terrible acts of atrocities? Right now, we have many questions. Keep checking in as we struggle to find what inspires what Maass describes as the “wild beast” living in every man.

Click here for more pictures of the trip.