Jane Mallach ’20 shares a powerful learning experience on the missing and unidentified immigrants crossing the U.S.- Mexico border.

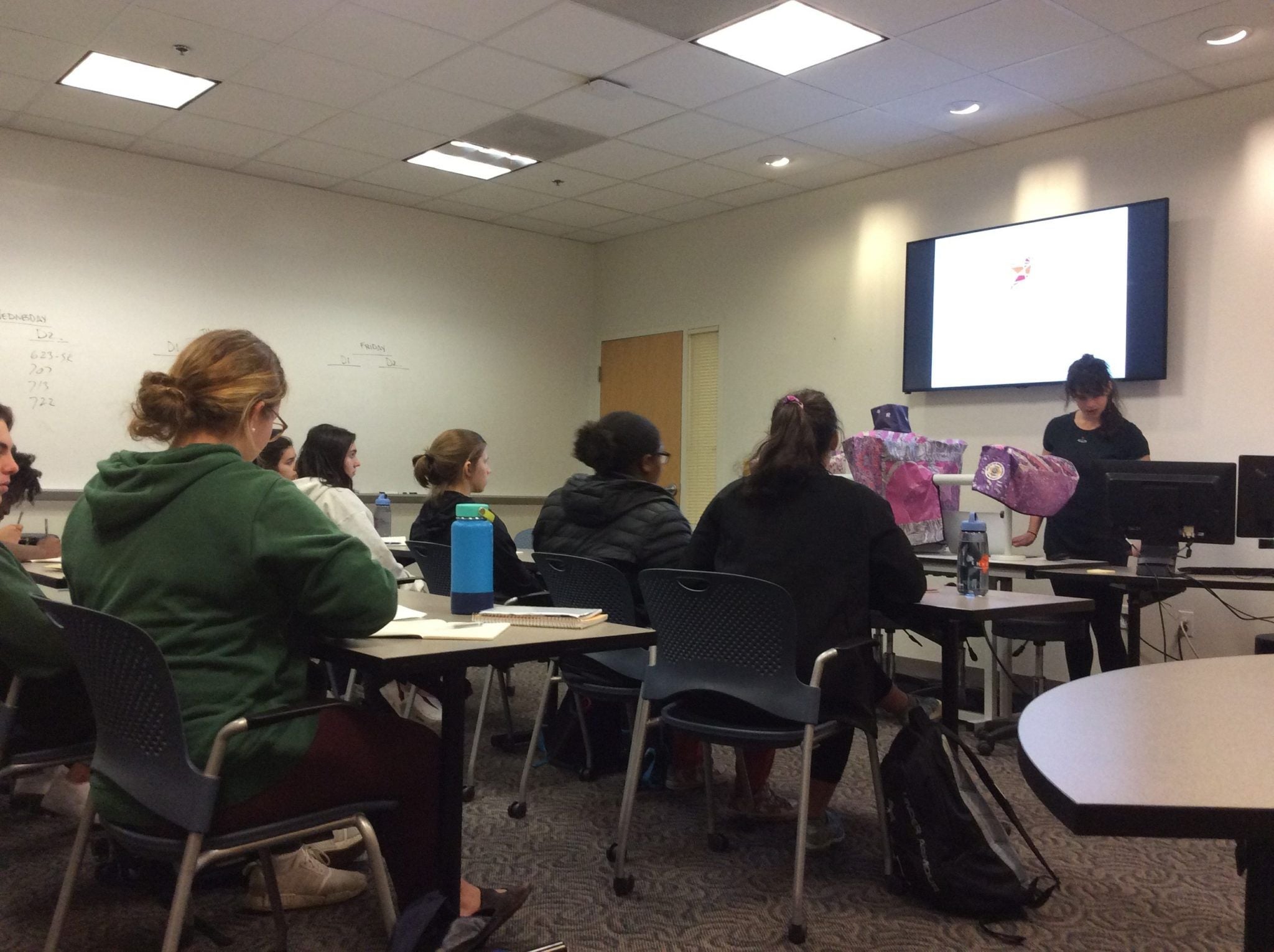

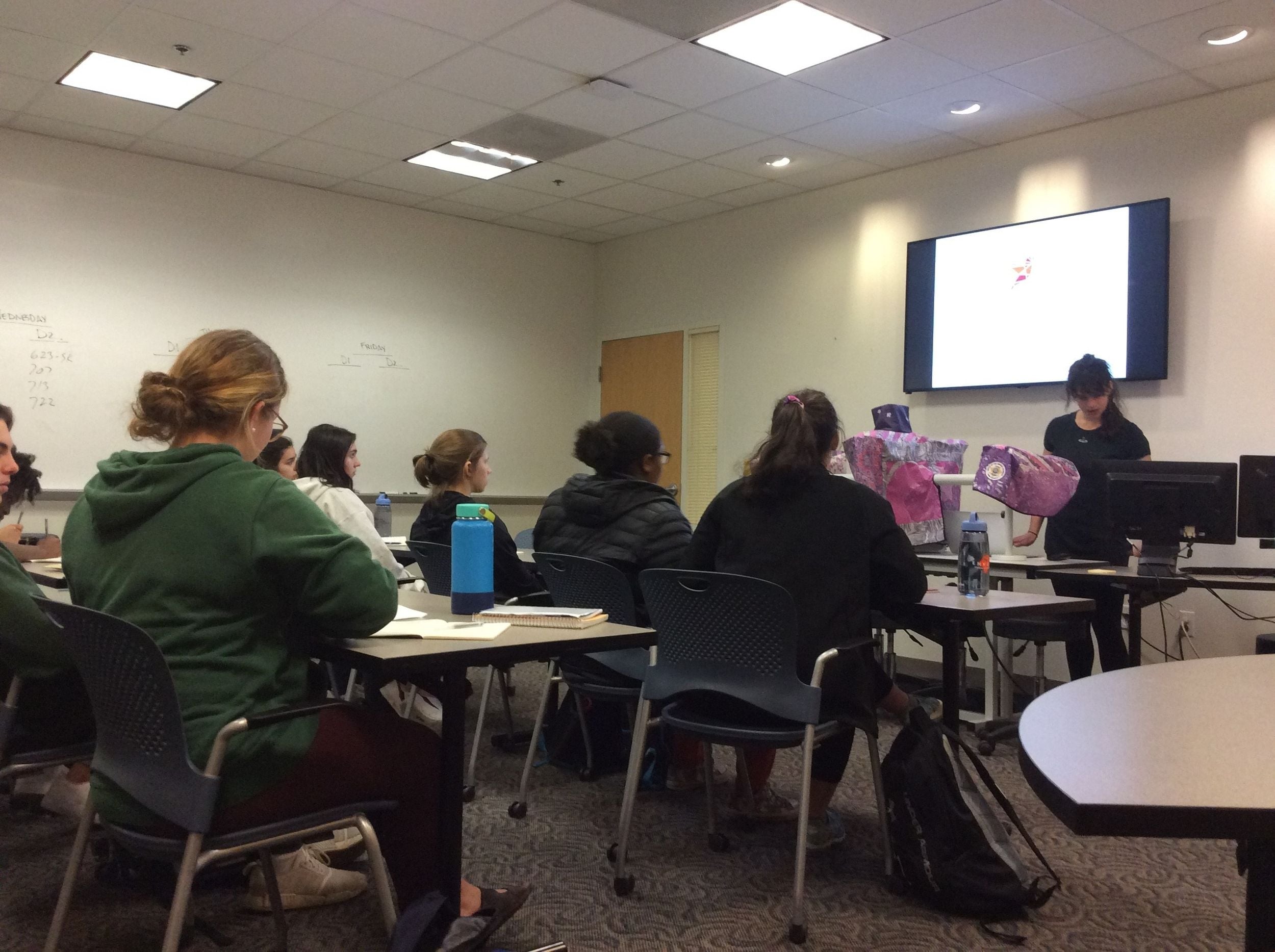

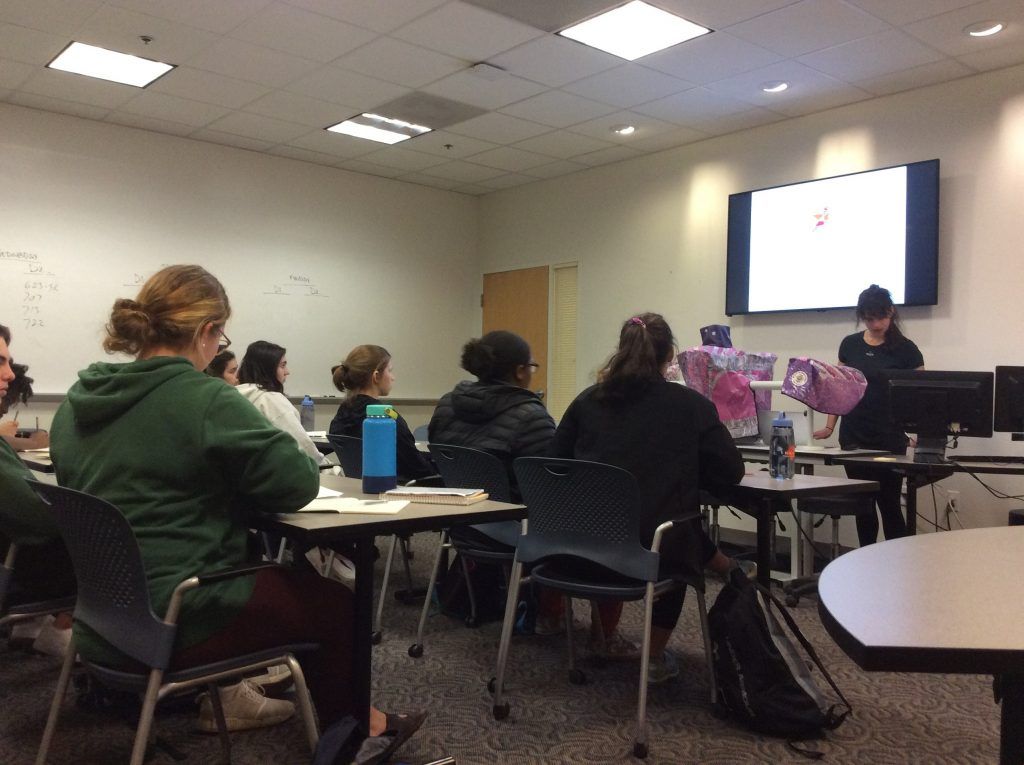

This afternoon we headed to the Colibrí Center for Human Rights. Once inside, we were led into a conference room to learn about the organization. Two women who worked there, Leah and Stephanie, enthusiastically presented to our group. Colibrí, an NGO that began in 2006 to work to address the high numbers of unidentified bodies of those attempting to cross the border. In fear of being deported themselves, undocumented immigrants are often afraid to report missing family members. Colibrí believes every person’s story and truth should be taken with justice and dignity.

We were surprised to learn that the border isn’t inherently dangerous and deadly, but rather the government has chosen to make it this way. “Prevention through Deterrence” is the name of the border security protocol creating an incredibly dangerous journey for migrants. The rationale is that by making the border as difficult to cross as possible, people will be too afraid to attempt it. But, with the closing off of the previously pass through ports of entry, those desperate to cross will do so through extreme dangerous remote parts. Barriers have been increased in many cases as a symbol. We were shown a picture of what has been added to the fence at the border recently such as mesh in between the slats of the fence so families separated by the border can’t even see each other. They have also added extreme barbed wire. We will be going to that very spot on the border on Sunday and will get to experience it for ourselves.

Colibrí informed us that over 7,000 people have lost their lives crossing the border. But, this is the number that border patrol reports, and it is estimated to be much higher. Once a family reaches out to Colibrí about a missing family member, the organization first conducts an extensive phone call. Through that phone call they try to obtain as many specific details as possible that might help with identifying a body, whether that be tattoos or a missing tooth. Once that 30 minutes to an hour phone call has been completed the organization tries to do initial comparisons to found bodies. If that proves unsuccessful they then try DNA collection of family members in attempt to find a match. If they are able to identify the missing person, Colibrí then switches to their social work side and helps to support the family.

Many families within the network in similar situations have banded together and formed a support system for one another. Although Colibrí is doing such hard and necessary work, of the around 4,500 missing people that were last seen crossing the border, only around 100 have been identified. The fact that Colibrí must exist, dedicated to returning the bodies of migrants to their loved ones, is telling of the current state of American immigration.